Ex-teacher still advocates for deaf

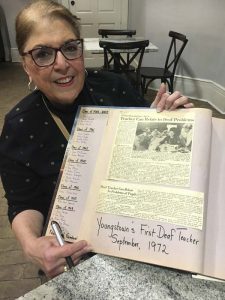

Correspondent photo / Sean Barron Retired longtime educator and advocate Irene Tunanidas of Poland holds a Dec. 17, 1972, Vindicator article about her being Youngstownás first deaf teacher. Tunanidas lost her hearing at age 3.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is one of a series of Saturday profiles of area residents and their stories. To suggest a profile, contact features editor Burton Cole at bcole@tribtoday.com.

POLAND — One man is teaching people who are deaf. Another has a lucrative career with the Department of Defense in Bloomington, Ind.

Both are deaf and both have one person in common — Irene Tunanidas was their teacher and advocate.

“One day in July, Jeff stopped at my home in Youngstown to share with me his decision to go to a trade school in Columbus,” Tunanidas recalled.

“I was glad, but I asked him if he knew what his IQ was, but he did not care about it. … I told him to think over about college and talk to his parents.”

After that seed had been planted, her former student passed the entrance exams he took in Tunanidas’ home to attend Gallaudet University, a Washington, D.C.-based federally chartered private liberal-arts school for those who are deaf or hard of hearing. Afterward, he earned a master’s degree from Western Maryland College in Westminster, Md., and teaches at the Ohio School for the Deaf in Columbus.

Perhaps part of the Poland woman’s strong advocacy on behalf of those who are deaf was borne of her own challenges. Tunanidas lost her hearing at age 3 from a double dosage of antibiotics intended to combat whooping cough.

In 1970, the 1966 Woodrow Wilson High School graduate earned a bachelor’s degree in art from Gallaudet. She was first exposed to sign language there as a freshman.

In public gatherings, she uses sign language interpreters who sign the conversations to her and can speak to the group what she signs back. Telephone offerings for the hearing impaired include text relay services. For this face-to-face interview, Tunanidas wrote most of her answers longhand on pieces of paper.

Tunanidas said that while pursuing a master’s degree in deaf education as a graduate student at Kent State University in the early 1970s, she was denied a sign-language interpreter, and a speechreading professor did not want Tunanidas in his class because, he claimed, the state’s public schools refused to hire teachers with disabilities.

Nevertheless, an adviser encouraged her to stay in the class, from which she received her only “C” grade, Tunanidas said.

The adviser then met several times in Columbus with the director of special education to have him issue a four-year teaching certificate for Tunanidas, which allowed her to graduate in August 1972 from Kent State.

Four school districts turned Tunanidas down before then-Youngstown City Schools Superintendent Dr. Robert Pegues accepted her on a trial basis. She taught at Stambaugh Elementary School from 1972 to 1978, by which time the Education for All Handicapped Children Act had been passed and signing was permitted in the deaf program, Tunanidas said.

While at Stambaugh Elementary, special assignments were delegated for some teachers, she said.

“Instead of teaching all subjects, (a supervisor) had five teachers teach one or two subjects,” Tunanidas said. “I was given fifth-grade language and social studies.”

Later, she was transferred to Wilson High because some deaf students’ parents were unhappy with a teacher “who was not resourceful or effective in work with deaf students,” the longtime educator said. Tunanidas added she also faced the challenge of working with deaf adolescents who were rebellious.

She faced another challenge while teaching English in the school’s deaf program, because a supervisor refused to honor Tunanidas’ request to have one of her students placed in a regular class, she said. The student prevailed after Tunanidas had the parents defend their daughter’s wish, which resulted in her being moved to the class for the second semester, Tunanidas said.

“I spoke up for my students by telling the supervisor to give them a chance to try out in the regular program,” she said.

The student for whom she advocated graduated summa cum laude in 2000 from Gallaudet with a major in psychology and works for the Georgia School for the Deaf in Atlanta.

After retiring from Youngstown City Schools in 2003, Tunanidas was offered a position in the Poland Local School District, where she tutored a student beginning in fifth grade who was born with craniofacial disorders. After graduating from Poland Seminary High School in 2011 with a 3.9 grade-point average, the student earned a degree in electrical engineering in 2018 from Akron University, then landed the job at the Department of Defense in Bloomington, she said.

Tunanidas’ laundry list of achievements over her long career also includes being a part-time American Sign Language instructor at Eastern Gateway Community College, teaching sign-language classes in Choffin Career Center’s Adult Education program and such classes at The Rayen School as well as Wilson and Chaney high schools.

She also completed counseling internships in Sacramento, Calif., and served as a cafeteria worker at Wilson High, a counselor-aide at the Youngstown Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation and as a tutor for deaf students at Warren G. Harding and Western Reserve high schools in Warren.

Tunanidas, who has volunteered for the American Red Cross, the Youngstown Hearing and Speech Center and Easter Seals’ Summer Volunteer Program, also has received numerous honors, such as the Hearing and Speech Center’s May Vetterle Award for Outstanding Community Service, the 1978 Outstanding Educator Award and, in 1992, the YWCA Woman of the Year Award in education.

But for Tunanidas, perhaps the largest award is being reminded of the impact she’s had on those she helped shape and mold.

“I keep in contact with several former students through Facebook and by videophone,” she said.

“Deaf students can succeed if their parents are involved in their school life.”